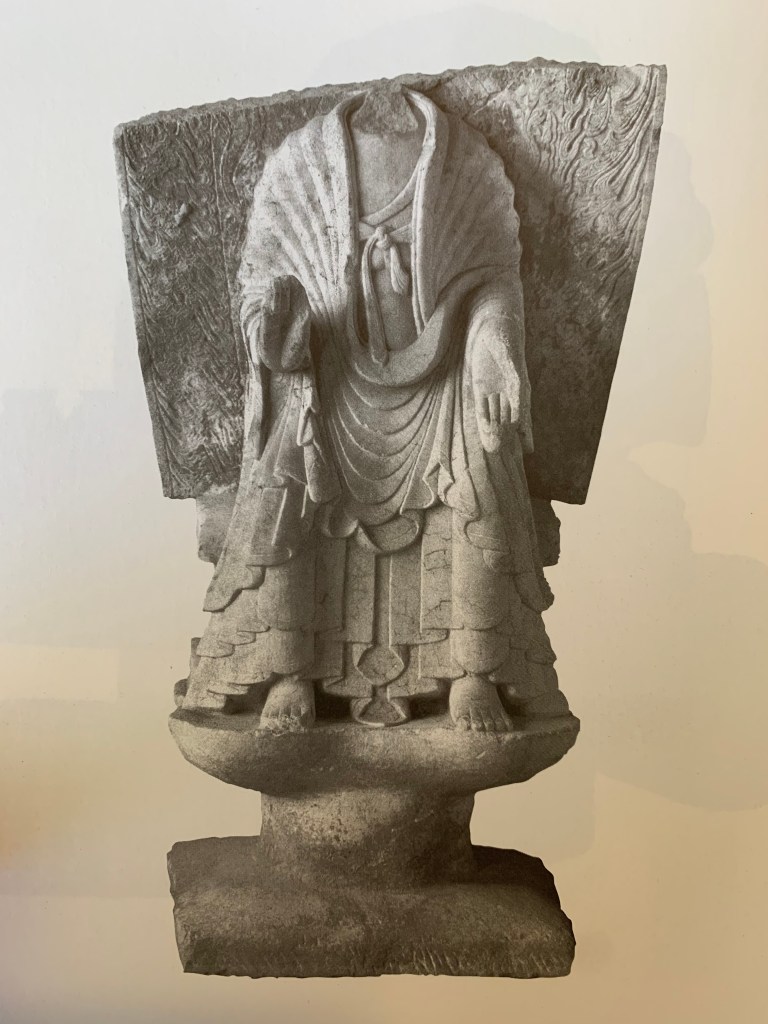

[Twitter, 1/26/23] MBOTD: Wang Nüren 王女仁, who inscribed an image on her parents’ behalf in 543 during the Eastern Wei. Put that way, it seems unsurprising, but what’s interesting is that the image itself had been commissioned 23 years earlier, in 520 during the Northern Wei. Here it is, with classic late N. Wei drapery. If you had to date it by style to either 520 or 543, it would very obviously be the former. It was found in the famous hoard at Xiudesi in Quyang 曲陽修德寺, Hebei. This image is from 李靜傑、田軍,定州白石佛像 (2019) p. 130:

The inscription reads: 武定元年九月八日,清信女王女仁興心造記。父母生存之日正光元年中,造像兩區釋迦、觀音。為國祚永康,三寶長延,兄弟姉妹,亡者歸真,現存得福,親羅蒙潤,眷屬得濟,一切含生,普得善願,一時成佛。It explains the gap between sculpture and inscription clearly: “In the first year of the Wuding reign [543 CE], on the eighth day of the ninth month, the pure and faithful daughter Wang Nüren resolved to make this inscription. In the first year of the Zhengguang era [520 CE], when my parents still lived, they sponsored two sculptures of Sakyamuni and Avalokitesvara, [in hopes] that the present dynasty long flourish, the Three Treasures long endure, and of my brothers and sisters, that the deceased should return to true form, and the living receive good fortune; that our relatives should flourish, and our family members gain relief [or, cross over the stream – a metaphor for enlightenment], and that all living beings should universally benefit from the benevolent vow, and all at once achieve Buddhahood.”

So it’s pretty clear that the parents commissioned two images (of which this is one – probably the Sakyamuni since it’s a Buddha and not a bodhisattva) but did not or were not able to have them inscribed. Why was that? The reason is not given, though we can speculate. Maybe the purchase of the images took all the funds the parents had to work with, and inscriptions cost extra. In the present day we tend to think of inscriptions as part of the commission, so it’s interesting to consider a case where they seem to have been separate. Many Buddhist images and monuments are dedicated to their parents by filial sons and daughters, so it’s not surprising to think that Wang Nüren might have been moved to commemorate her deceased parents by adding the inscription that records their intentions for the figure. The parents gained merit, in the usual way, by their dedication of two images. Was the addition of the inscription a filial duty meant to complete their act of merit-making, or was it analogous to Wang commissioning a sculpture in her own right for their benefit?

Cui bono? This example lets us frame the question, but doesn’t answer it. Given the fungible nature of merit, which can be earned by one person and ascribed to another’s benefit, there may not be a single clear answer. Is Wang Nüren a donor (in the sense of 功德主) here? And why was the job left to a daughter rather than a son? I don’t know, but it makes me think more about the economics of merit-making and merit exchange which are clearly at work here, perhaps informed by contemporary ideas about filial duty – which is interesting.

Leave a comment