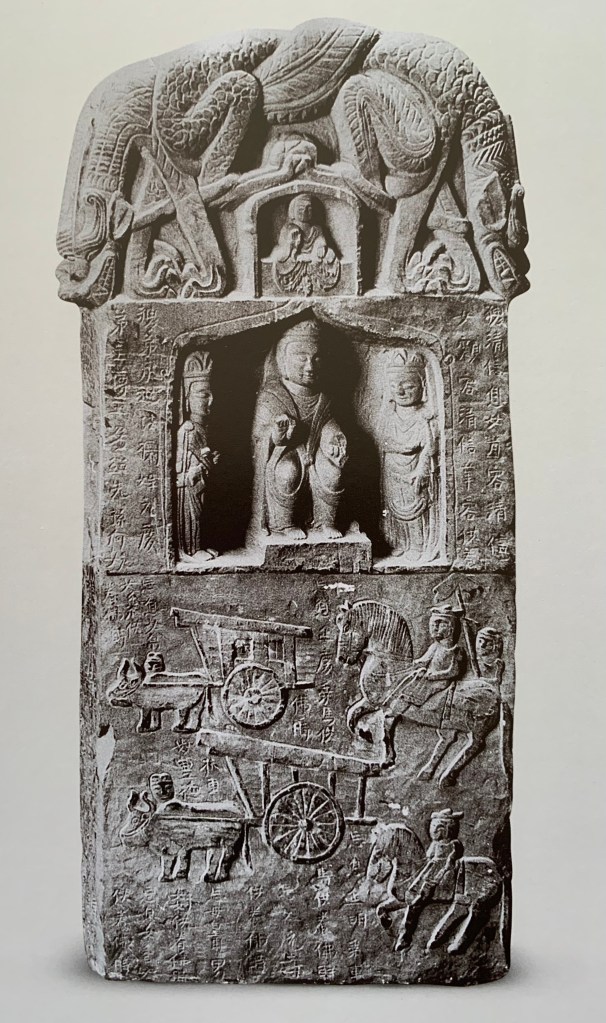

[Twitter, 1/17/23] Medieval Buddhist of the Day: Fengde, the oxcart groom. Fengde is commemorated on the N. Zhou stele of Wang Lingwei 王令猥 and family, dated 573, from Zhangjiachuan 張家川 county, now held by the Gansu Provincial Museum. Shown here: the back side of the stele.

Today I’m principally interested in those oxcarts and mounted figures, hence the back view. However, if you want to see a rotatable 3-D model of the stele, there is one here for some reason.

Anyway. Oxcarts. So the male figure mounted on horseback usually signals a high-status donor in Northern Dynasties Buddhist art. He may be accompanied by attendants, as here, where the uppermost mounted figure has a servant holding a canopy over his head. The oxcart is the female equivalent: the high-status woman travelling modestly enclosed, shielded from the eyes of the public. So an enclosed oxcart can actually be a female donor portrait, even though you can’t see the donor herself (which is, of course, the whole point). (There’s an excursus to be made here about similar imagery in contemporary tombs, such as the double tomb of Xu Xianxiu and his wife, in which his horse and her oxcart await their journey to an afterlife beyond the tomb. Maybe another day. It’s my turn to cook supper.)

A proper lady does not, evidently, drive her own oxcart; she has a servant to do it. In fact, servants and attendants are everywhere among the donor portraits of the Northern Dynasties, typically holding canopies or fans and signalling the status of their employers. Despite this, it doesn’t seem that servants and attendants themselves “count” as donors in the strictest sense. They disappear into an odd little vacuum of identity, much like the usually nameless artisans who carve the images and monuments in the first place. The language of donor inscriptions elides the work of many hands, crediting the donor with “making” (造) the monument when what the donor actually did was *pay for* the monument. (It also hampers our ability to understand the relationship between donor and artisan).

Given the term “make” (造), one would think that artisans should accrue merit themselves for bringing Buddhist images into being, even though they were paid for it. But we don’t really know how or whether this worked – there just isn’t enough documentation. Similarly, given the way donor figures are visual representations of merit-making, surely the servants who carry the flowers and incense and other offerings (or, as I’ve sometimes seen, stand to one side holding their employer’s sword and gear while he makes offerings) could also be seen to accrue merit? But in most cases they appear to be there simply as status symbols – they are attributes of their employer, rather than people in their own right. Were they Buddhists? How would we know if they were?

A donor could be anyone, in theory: a modest image in the Guyang Cave at Longmen commemorates the sedan-chair bearer Zhang Yuanzu (步轝郎張元祖), sponsored by his wife. Even so, there were doubtless those who could not muster even minimal resources for something like this. But servants and attendants are typically anonymous figures on monuments like this one, which is why Fengde is an interesting exception. The mounted figures and oxcarts are labeled with the names of the donors they represent: The uppermost mounted figure is labeled 亡息延慶乘馬供[養]佛時 “When the deceased son Yanqing rode a horse to make offerings to the Buddha,” and the oxcart, 王息女帛女乘[車]供養佛時 “When Wang’s daughter Bonü rode a cart to make offerings to the Buddha.” This is interesting in the way it calls attention to the horse and the cart, which is unusual. The lower two figures are similarly inscribed, but then, above the ox’s back are the words 扶車奴豐德 “The bondsman who leads the oxcart, Fengde.” Why was he picked out? The term “bondsman” 奴 indicates a kind of unfree status, but not necessarily chattel slavery. Several people including Scott Pearce and Yi-t’ung Wang have written about such roles in the Northern Dynasties, but I’ll have to go back to the literature for a refresh.

In the meantime, however, I wanted to draw our attention to Fengde, one of the only named servants I can think of in the Buddhist epigraphic record in this period. Even not knowing much about what his life was like, we can still remember him.

Leave a comment