[Bluesky, 6/12/24] How realistic do your little guys need to be in order to ensure that they turn up in your afterlife? A post about tomb figurines.

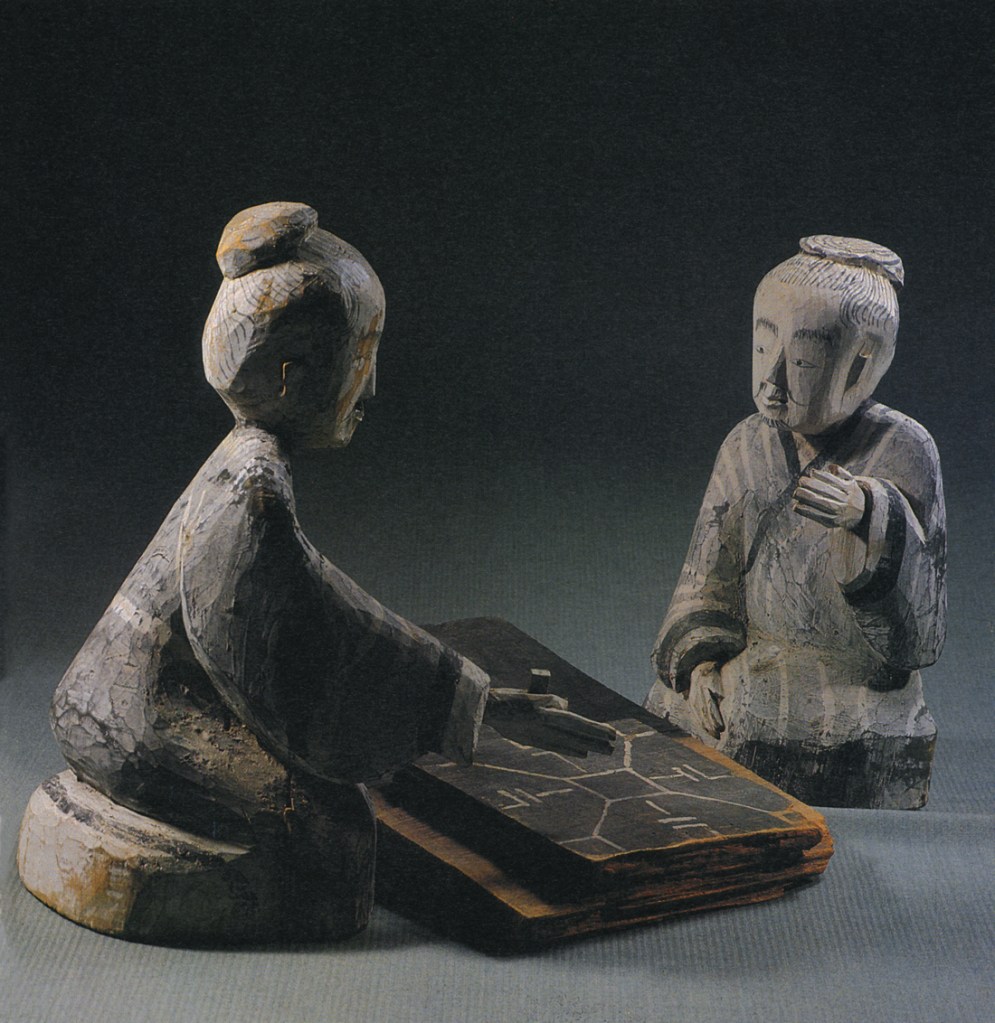

(Han tomb figurine, men playing the game of liubo)

Ancient Chinese elite tombs (of the prehistoric and Shang periods and into the early Zhou) often included two kinds of dead people besides the principal tomb occupant. The first kind were 人祭, human sacrifices who were treated much like animal sacrifices, and the second kind were 陪葬, those who accompanied the deceased into the tomb – servants, entertainers, charioteers etc. Presumably the latter were meant to accompany the deceased in the afterlife as well. Early tombs also contained a range of real things a person might need (food, clothing, money, weapons, horses etc), suggesting an afterlife much like this life, with similar needs for sustenance, shelter, travel, and entertainment. Later descriptions of life after death support this.

However, as (I assume) in other cultures which permitted this kind of thing, eventually the morality of killing perfectly good humans in order to provide servants for other, more high-status humans after the latter’s death seems to have been increasingly called into question. By the middle Zhou, increasingly, elite burials were furnished instead with *replicas* of things the deceased might need in the afterlife, including miniature figures of servants, entertainers, charioteers etc. This was probably a great relief to servants, entertainers, and charioteers. The replicas, usually made in pottery (north China) or wood (south China), were usually recognizable but simplified representations of the things they were meant to provide, such as this 5cm pottery figurine from a Zhou tomb, which has a rudimentary face and no hands or feet.

Wooden figurines from the region of Chu in the south were often more detailed and painted beautifully in lacquer, but they were still stylized representations, and rarely more than 30cm in height.

Clearly such figures could be efficacious without strongly resembling the human servants they represented, either in detail or in scale. An entire line-up of tiny clay musicians could evidently mean you would enjoy the services of a real private ensemble in the afterlife.

In fact, there’s some evidence to suggest that objects made for the use of the dead (明器, “spirit objects”) were supposed to be distinct from objects used by the living – and Confucius himself purportedly frames this as a moral imperative to avoid human sacrifice. He suggests that spirit objects should not closely resemble their real-life counterparts: 孔子謂:為明器者,知喪道矣,備物而不可用也。哀哉!死者而用生者之器也。不殆於用殉乎哉。其曰明器,神明之也。塗車芻靈,自古有之,明器之道也。孔子謂為芻靈者善,謂為俑者不仁,〔不〕殆於用人乎哉。 「禮記,壇弓下」In condensed translation: “Confucius said that those who made spirit objects understood the mourning rites indeed, for the objects were complete but none could be used. How regrettable, when the dead use objects belonging to the living, for this is nearly the same as the living being buried alive as a sacrifice. Spirit objects are so called because the spirits perceive them. Clay carts and straw figures have long been used as spirit objects. Confucius said that making straw figures was praiseworthy, whereas making images was inhumane, for this is nearly the same as using living people.” In other words, spirit objects which too closely resemble the human figures they represent are morally hazardous, because they come too close to the immoral practice of human sacrifice. And during the Warring States, this seems to have remained the standard.

But then along comes this guy. The first emperor of Qin, with his terra-cotta army of life-sized soldiers. He famously didn’t care what Confucius thought. But also, these figurines reflect a kind of quantum leap in representation and realism, which many scholars have wrestled with.

I’m less interested in tracing the source of this artistic change, and more interested in why you would bother to build seven thousand life-size soldiers, plus horses, grooms, acrobats and performers, and whatever else is still out there on the Lishan site, awaiting discovery. The First Emperor was a more-is-better guy, and there is a perceptible sense here of doing the thing better and to a greater extent than anyone had done it before. By all reports he didn’t care about saving lives and in fact had some of his concubines follow him in death. But: The terra-cotta army and related materials from the site suggest the thinking about representation and the afterlife was getting more complicated. What if the striking realism of the figures was a way of making sure they manifested in the afterlife as the emperor required?

For example, although the soldiers are demonstrably NOT portraits of individual people (contrary to what tour guides at the site will tell you), they are distinguished from each other with details of hair, beards, etc. – perhaps because an army is composed of individuals. They are not, in absolute terms, all that naturalistic – their legs are like water pipes, they only kind of have elbows, there is no apparent human body under their uniforms which are so carefully distinguished by rank. But evidently that was realism enough for the purpose. Other finds at the site invite us to ask what constitutes adequate levels of representation. Terra-cotta horses are found in some cases with tack modeled onto their surfaces, much as the soldiers wear their armor, while other horses were provided with real tack (and real chariots). The terra-cotta soldiers in their molded-on armor had real bronze weapons. A pair of imperial chariots in bronze are half-scale, but cast in multiple pieces and assembled carefully (including all the horse gear, which is cast separately from the horses). If all of these things were meant to arrive in the afterlife in their usable forms, the standard of realism that makes them efficacious is much more stringent than in the Zhou. It seems to show signs of experimentation, or at least of interesting variability.

It’s the terra-cotta armies produced *after* the Qin that really drive home the idea that there was some relationship between representation and efficacy for these later tombs. Take, for example, the terra-cotta soldiers of Emperor Jing of the Han Dynasty. His tomb, the Yangling mausoleum, contained among other things thousands of terra-cotta servants and soldiers at half life-size. The figures are modeled as anatomically correct, armless male and female nudes, with points for mounting wooden (possibly jointed) arms.

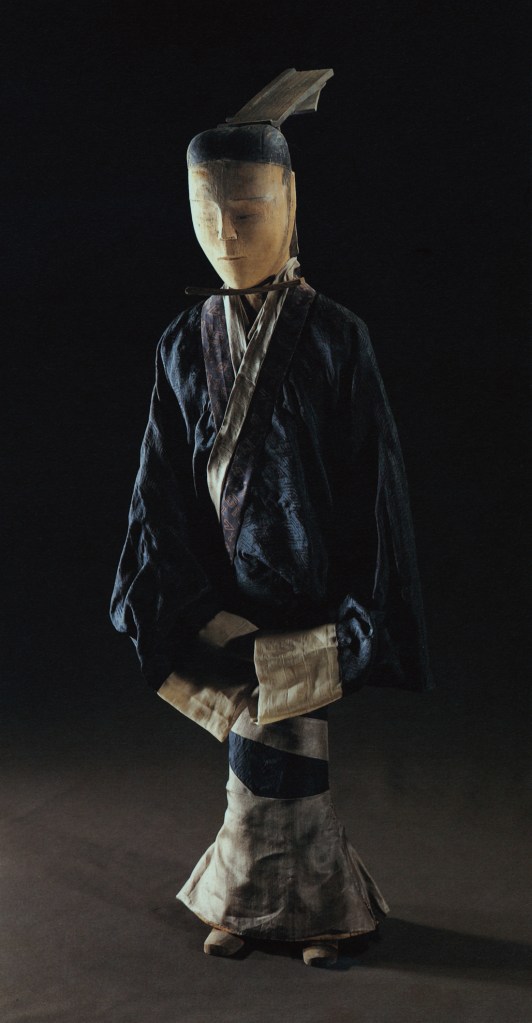

It seems likely that the figures were dressed in real clothing, much like this (smaller) steward figure from the Han tombs at Mawangdui. No arms or clothing survive at Yangling, but then it is hard to imagine the soldiers and servants going into the earth as armless nudes.

Which is more realistic: a life-size figure with an individualized face, whose body is not represented under its clothing (as the Qin army), or a half life-size figure with a generic face but moveable, perhaps poseable arms and dressed in real clothing? And could the difference have been thought to matter to the figurines’ efficacy? Later Han tombs tend to return to the use of miniatures, often toylike in scale, including figures but also farm animals, granaries, wells, stoves, looms, farm equipment, and architectural models. Many Han figures are wonderfully expressive, from the elegance of a sleeve dancer to the humor of a storyteller with his drum. Others are quite utilitarian. But I can’t think of later examples that explore the problem of representation quite like the Qin-Han examples.

Leave a comment